Facet joint bone spurs can grow on the interior or exterior of the zygapophyseal structures causing mechanical or neurological pain. In facet syndrome, there are several distinct ways in which bone spurs can enact symptoms directly in the joint, as well as in the surrounding spinal anatomy. Of all the facet joint-related diagnoses, bone spurs account for the majority of symptomatic expressions involving the apophyseal structures.

Arthritic bone spurring is a process that is a direct result of other spinal degenerative changes. Spurring occurs throughout the skeletal structures of the anatomy and is focused in areas where joint activity is significant. Bone spurs can not be accurately diagnosed without the benefit of advanced imaging studies, such as x-ray, CT-scan or MRI. Clinicians might suspect spur formation from a patient’s symptoms and physical exam, but this theory can not be confirmed without some types of internal visualization study.

This essay seeks to define and explain bone spurs in the facet joints. We will provide an analysis of the pathological potential of bone spurs and the ways that they can create pain in the spine. However, we will also objectively view arthritic spurring for what it truly is: a normal part of human aging. This is part 1 of a 2 part series on facet spurring.

What are Facet Joint Bone Spurs?

Bone spurs, also known medically as osteophytes, are completely normal to experience as a person ages. These spurs form in many areas of the spine, but are most often associated with the various spinal joints and other areas that tend to encounter bone-on-bone contact as age progresses. Spurs can be tiny, small, medium, large or huge. Smaller spurring is more common, while the incidence of larger osteophytes decreases as the size of the spur increases.

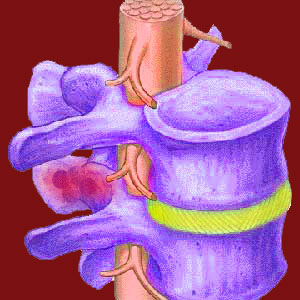

Bone spurs are outcroppings of skeletal tissue that form on bone surfaces or result from the ossification of previously soft tissues. Spurs can literally grow off the surface of a bone or may form when particles accumulate and fuse together, joining themselves to existing bone in the greater spinal anatomy. When it comes to facet joint spurring, the location of the osteophytes varies. Many osteophytes form within the joint itself. Others might form on the edges of the joint, where the 2 vertebral bones meet. Some spurs even form outside of the facet joint, but in close proximity. The location of the spurs is usually the main factor in determining if they will be symptomatic, since particular placements might interfere with normal joint movement or may also compress neurological tissues.

What Causes Bone Spurs?

Bone spurs in the zygapophyseal joints form from the same processes that cause most osteophytes to form. Spurs are part of the larger osteoarthritic process that affects the major and minor joints of the body. There is no single cause of spurring, but instead there is usually a combination of factors that all work together to encourage osteophyte growth:

Disc desiccation causes the intervertebral structures to shrink in mass and thickness. Disc desiccation also encourages breakdown of the annulus fibrosus that might enact herniation of the disc tissue. These circumstances decrease the effective thickness of the cushion in between vertebral bones. Disc degeneration is a completely normal and universal process and is not at all harmful unto itself.

Simultaneously, the protective measures built into the facet joints erode and deteriorate with time and physical activity. The cartilage which covers the bony joint surfaces disintegrates, while the synovial fluid dries up in the joint capsule. The result is less lubrication for the joint, creating rougher interactions between bony surfaces. Since these surfaces are no longer adequately protected against contact, they interact more often and more violently, causing friction and small imperfections in the joint surface. Interaction between bones also creates debris in the form of particles that break free due to the skeletal surfaces rubbing together. Once again, this degeneration is expected and not inherently painful to any significant degree.

Facet Joint Bone Spurs Locations

Anatomy is wonderful in its diversity. Appropriately, facet joint bone spurs can from in many areas of the joint. Statistically, most of the particles will tend to cling to bony regions in areas of less interactive activity. This is because the bony meeting of joint components is continuous and tends to discourage the growth of spurs directly on the interacting edges. However, this is not an absolute rule. When spurs form “out of the way” they are rarely symptomatic and can accumulate without changing joint functionality. Occasionally, these spurs might impinge on the tiny nerves that innervate the facet joint, but this is not common.

When bone damage occurs directly on the areas of bony interaction and spurs do begin to form there, the chances increase for the development of facet joint syndrome. These spurs can create mechanical difficulties for the joint or might actually form in locations that encroach on the neuroforamen, of which the facet joints form the posterior border. These are the spurs that tend to become pathological and require treatment.

Facet Joint Bone Spurs Synopsis

This report serves as a primer to the mechanism behind most cases of facet joint syndrome. Of course, some cases are caused by other factors, such as ligament laxity or tension issues and are not necessarily motivated by spur formation. However, these exceptions account for a minority of facet syndrome diagnoses.

We continue our coverage of facet joint spurring in part 2 of this essay, titled facet joint osteophytes. In the second part of this patient guide, we provide a detailed accounting of how spurs create symptoms, as well as how some spurs are mistakenly blamed for generating facet syndrome.

Facet Joint Pain > Facet Joints > Facet Joint Bone Spurs